Who’s this?

You knew at first glance, didn’t you? Even without facial features or a corresponding story, it’s clear that this is a silhouette of Sherlock Holmes.

Full disclosure: I’ve never read any of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s original stories or novels. I’ve read Neil Gaiman’s “A Study in Emerald.” I’ve seen the first Robert Downey Jr. film, and plan on seeing the second. And, of course, I’ve seen the wonderful TV series written by Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss. Yet, despite never having read a single word of Conan Doyle’s, I can describe what Sherlock Holmes looks like. Deerstalker cap. “Inverness” cape. This image of Sherlock, literature’s most famous detective, has come to be used like a proprietary eponym; as a symbol for detectives in general, or as an icon on the spines of books indicating that they are in the mystery genre. It could be argued, and has, that the person responsible for the look of Sherlock is as responsible as Doyle, if not more, for the character’s longevity in the pop culture consciousness.

Well, if that’s the case, I guess we’d better shine a spotlight on him during Sherlock Holmes week, huh? Let’s get to know famed illustrator, Sidney Paget.

Sidney Paget wasn’t even supposed to get this job. The Strand, the British magazine that first published Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories in July 1891, mistakenly sent him the letter of commission for the illustration job rather than send it to his brother, Walter Paget, also an illustrator.

Oooh! Burn! Then again, Walter Paget has been called the “least talented” illustrator amongst the Paget brothers, so had he gotten the job, the Sherlock Holmes illustrations might not seem as prestigious as they do now. Who knows?

What we do know is that Sidney Paget studied at the Royal Academy of Arts and had a successful career outside of his work for The Strand. He was well-regarded in the industry for his work in such publications as Pall Mall Magazine, the Illustrated London News, The Graphic, and The Sphere. He also provided illustrations that popularized another detective series: Arthur Morrison’s Martin Hewitt character was sort of the anti-Sherlock (in much the same way that Artemis Fowl is the anti-Harry Potter), and Paget’s illustrations were responsible for popularizing that series of stories in its time. But there are benefits to being the character that came first, and Sherlock came first, meaning that Paget’s illustrations were able to launch an already novel character into the stratosphere by providing an indelible image that would not only be popular to readers at the time, but would become associated with the character long after the writer’s and illustrator’s deaths.

Sidney Paget was not the first person to draw Holmes. That distinction goes to David Henry Friston, who illustrated A Study in Scarlet which, along with the novel The Sign of the Four, came before Conan Doyle’s first Sherlock story in The Strand, “A Scandal in Bohemia.” Paget’s ultimate success with the character is interesting when considering Friston’s original illustrations. Here’s one of Friston’s illustrations from A Study in Scarlet:

The silhouette is very similar to the one we know, but it’s….off somehow. Sherlock’s hat is curved, sort of like a deerstalker cap, but it seems to be more of an overstretched bowler. His coat is kind of like a cape, but it’s more an elongated trench coat. It’s as if Friston had an instinct about the character, but chose to ignore it in favor of clothing that Victorian readers might be more ready to accept on a protagonist.

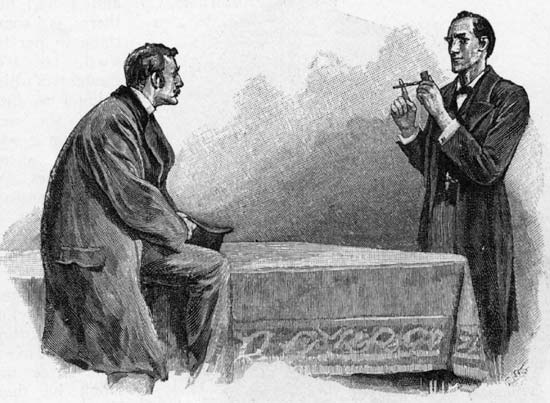

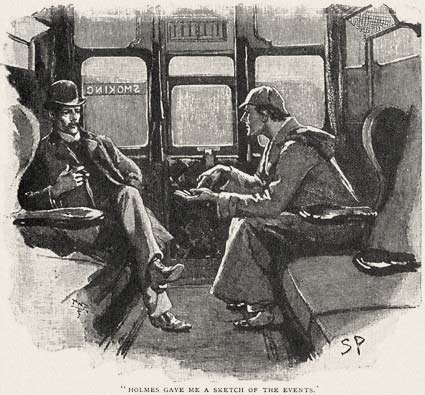

But it wasn’t this look that caught fire. It was Paget’s take on the character that did. But why? Here’s an illustration from “Silver Blaze”:

Whereas the Holmes of Friston’s illustration seems as blocky and bumbling as the police officers with which he’s surrounded, one could never mistake the Sherlock of Paget’s illustration for a mere police officer. In the stories, Watson describes Holmes as “bohemian” and “eccentric,” but he is also clearly an upper-class, university-educated man with a sense of fashion and propriety. This may be why Paget only depicted Sherlock in the deerstalker cap and Inverness cape in appropriate situations, like when he was working out in a rural setting, or traveling cross-country like in the above illustration, or the first time he dons the get-up in “The Boscombe Valley Mystery.” However, the choice of garb also suggests something about the character that I think was intentional. Sherlock isn’t just a consulting detective. He’s a hunter—methodical, patient, and constantly springing back waiting to pounce or come out from behind something and yell “Ah, HA!” The Sherlock of Paget’s illustrations seems comfortable in or out of the hat and cape, which speaks to his bohemian nature. Whether in a Victorian drawing room, or wandering around the grounds of a country estate, Sherlock is always at home and always entirely himself—as long as he’s on a case.

In this essay on the illustrations for “A Scandal in Bohemia,” the author (sadly, I couldn’t find his/her name) says “[‘A Scandal in Bohemia’] was the first story illustrated by Paget. In it he established not only recognizable features that would become synonymous with Holmes and Watson, but he also established an air of confidence and sureness of action that would be the foundation of their relationship and their cases. Paget makes us see the English in the characters. And therein lies the magic.” It isn’t just the hat and cape. Paget’s illustrations capture the dynamics of Holmes and Watson, both in relation to each other and to other characters in a way that illustrators after Paget tried desperately to imitate. The choice of deerstalker cap and Inverness cape also emphasize the Britishness of the character, which may be another reason why that particular image is so indelible. Paget’s choices make the character specific. Sherlock Holmes isn’t just any consulting detective. He’s a resolutely British one, and Paget chose to emphasize those things, rather than try to make him “universal.” It is that kind of specificity that makes a work of art survive the test of time.

I first learned about Sidney Paget at Geek Girl Con back in October, when I went to a Scott Westerfeld panel and he did an amazing presentation about the importance of illustration. Using Paget as an example, he showed how important an illustrator could be not only in creating a work of fiction, but in sparking the imagination of the reader. He regrets that, for some reason, we’ve gotten it into our heads that illustration is the sole purview of children’s books and comics, and that the common argument against “pictures” in books is that it stifles the imagination, when illustrations used to accompany most books for adults! Meanwhile, I regret the fact that short fiction, which once had a permanent home in mainstream publications seems to have gone the way of the dinosaur (or worse, the way of the underperforming short story collection). Perhaps, remembering successes like Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories and Sidney Paget’s timeless illustrations might help us remember what it is that people love about fiction. Not all stories with pictures are for children. We’ve started to accept this with comics and graphic novels. However, that medium is mostly pictures with fewer words. There is a way for prose stories to benefit from the use of well-placed and beautifully-drawn illustrations. Here’s hoping that, by remembering the work of Sidney Paget, we remember how to go about doing that.

And now, I’ll leave you with a photo of Sidney Paget in a deerstalker cap. It seems appropriate.

Teresa Jusino likes pictures. She can be heard on the popular Doctor Who podcast, 2 Minute Time Lord, participating in a roundtable on Series 6.1. Her “feminist brown person” take on pop culture has been featured on websites like ChinaShopMag.com, PinkRaygun.com, Newsarama, and PopMatters.com. Her fiction has appeared in the sci-fi literary magazine, Crossed Genres; she is the editor of Beginning of Line, the Caprica fan fiction site; and her essay “Why Joss is More Important Than His ‘Verse” is included in Whedonistas: A Celebration of the Worlds of Joss Whedon By the Women Who Love Them, which is on sale now wherever books are sold! 2012 will see Teresa’s work in an upcoming non-fiction sci-fi anthology. Get Twitterpated with Teresa, “like” her on Facebook, or visit her at The Teresa Jusino Experience.

Although it’s true that Paget does portray Sherlock Holmes with the deerstalker cap in a few of his stories (and always when Holmes was out in the country) the common association with the deerstalker cap and curved pipe does not come from Conan Doyle or Paget, but from William Gillette’s portrayal of Holmes onstage.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Gillette

The use of the Inverness cape is from Basil Rathbone’s portrayal of Holmes from films from the 30s and 40s (along with the catchphrase “Elementary, my dear Watson”, which Holmes never actually says in the books.)

In other words, although Paget did illustrate Holmes wearing such items of clothing a few times (out of hundreds of illustrations), it was certainly not a “costume” that distinguished Holmes from other men of the Victorian age. I would say that Paget is more famous for portraying Holmes’ physical look – the skinniness, the big forehead, and Dr. Watson’s too.

I think you may have missed a factor here. I’ve been researching William Gillette, an actor who became famous portraying Holmes on stage, and most of the material I’ve read says that Gillette introduced the deerstalker cap and Inverness cape. Paget added them to the illustrations when Gillette became so popular.

On the other hand, if I’ve got the wrong end of the stick here, I’m sure we’ll find out shortly now. (g)

@2 the first story in which Holmes is depicted (by Paget) wearing the deerstalker is “The Boscombe Valley Mystery.” This was published in 1891, welll before the Gillette play which debuted in 1899.

I have also heard that it was Gillette who introduced the deerstalker and cape in the early stage plays. I appreciated the Jeremy Brett TV series because he seldom wore the “costume” as it eventually became. Wearing a deerstalker cap around London would be the equivelent of wearing those floppy fisherman hats with hooks on them in polite society. Victorians would be aghast.

Gillette definitely used the deerstalker cap and Inverness cape because of Paget’s illustrations, not the other way around. However, Gillette IS credited with other additions to Sherlock, like his pipe, for example.

I’m reasonably sure that the example of the Paget illustration is not from the Scandal in Bohemia. My first instinct is “Silver Blaze” (of the “Curious incident of the dog in the night-time” fame), the very beginning as they venture to Dartmoor. I’m not sure, because my facsimile editions aren’t at hand, but my (not facsimile) copy of the story which is at hand certainly has that illustration.

Further, I’m not sure I can agree with the article. While Holmes has an iconic silhouette, that’s not entirely to Paget’s credit. The meerschaum pipe and deerstalker ensemble is, as was rightly pointed out, is mostly a theatrical invention. Doyle, and by extension Paget, tended to dress Holmes in appropriate clothes for the time. That means that the hunting cape and deerstalker are reserved to trips to the countryside (that’s why they are there in the Silver Blaze illustration) . To wear them about London would, if what I’ve read is correct, seemed garish and inappropriate to the Victorians. The Jeremy Brett series is generally faithful to the source material and in it you can see Holmes in a top hat as likely as in a deerstalker.

All that nitpicky stuff being out of the way, I do agree with the general thrust of the article. Illustration used to be an important element of books. The fact that it isn’t anymore is kind of sad. As Terry Pratchett pointed out “I conceived the Discworld, Josh Kirby created it”.

@6. Yep! I caught that “Silver Blaze” error eariler. It’s been corrected! :-)

Veljko @6 –

I mentioned this in my article, the fact that Paget only had him wear the deerstalker cap when it was appropriate, and it’s why I have so much respect for Paget. Paget wasn’t trying to design a uniform, but he did what he did so well that theatrical and film productions were able to latch on to specifics. You could argue that it’s the theatrical productions that “made” them iconic, but they got their inspiration from somewhere, and it was from looking at Paget’s illustrations. They didn’t come up with that imagery whole cloth.

And sorry about the mistake w/the illustration I attributed to “A Scandal in Bohemia!” The internet isn’t the most reliable place, and while I discovered the mistake before I posted the article, I forgot to change it! This is why I’m glad there are people who’ve ACTUALLY read the Holmes stories to correct this stuff! :)

You really ought to try reading some of the stories–there’s a reason they are so famous

Rea: They are indeed good stories, which is why we’re all so interested in their epiphenomena.

@rea – I KNOW! :) It’s funny, because I love all the retellings, and I’m a HUGE fan of Moffat’s Sherlock series….but I’ve just never read mysteries, and so I’m a bit hesitant. I really should get over it, shouldn’t I?

Great to read a piece on illustration and agree that it is very sad that it has dropped out of fashion so spectacularly that the Harry Potter books were unillustrated which would have been unthinkable a few decades ago. Ah well.

Is there a film/TV version where Holmes always wears the deerstalker/cape combo? I can only think of Murder by Decree with Christopher Plummer in that get-up which somewhat spoils for me what is a rather good version of the character.

a-j @14 – well, the Harry Potter books weren’t entirely unilllustrated. Credit where credit is due! :) The Harry Potter books did have small illustrations accompanying each chapter by Mary GrandPre.

But you’re right. Decades ago, a book like Harry Potter would’ve had full-page illustrations.

Love a mystery? Come to the 13th Love is Murder Mystery Conference for

Readers, Writers and Fans, Feb. 3-5 in Chicago at the Intercontinental

Chicago O’Hare Hotel. Mingle, network and dine with fellow mystery

readers and authors; learn from publishing, writing and forensics

experts; meet featured authors Donald Bain, Julie James, David Morrell

and Hank Phillippi Ryan; pitch your book idea(s) to NYC and Chicago publishers and agents;

All-inclusive $349 package includes all panel discussions, workshops,

meals and special events. Rooms are available for $89/night for up to 4

nights (Thurs-Sun)… or just come for a day, the Saturday afternoon tea

party, or Saturday evening banquet.

Here’s the URL for the Love is Murder conference: http://www.loveismurder.net

The Inverness Cape? Paget seems to show Holmes wearing an overcoat with a hood, not a cape.